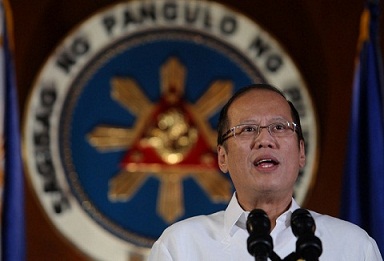

FIGHTING corruption has been one of the top priorities of President Benigno S. Aquino III. Or so he claims. He bannered the slogan “kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap” during the 2010 presidential campaign.

He promised to be the “most-determined fighter of corruption” in his Social Contract with the Filipino People, the Aquino administration’s platform until 2016.

He also made good governance a cornerstone in the current Philippine Development Plan, promising to curb corruption by intensifying government efforts at detection and prevention as well as resolving pending corruption cases with dispatch.

Read, Part 3 of our series on ‘Pork a la Gloria, Pork a la PNoy’:

Yet barely a year before Aquino’s term ends, the Aquino administration seems to be falling far, far behind in fulfilling such pledges. Indeed, one of the starkest examples of its weak response to corruption is its action – or lack thereof – on the controversial cases involving pork-barrel monies.

In fact, rather than being proactive in pursuing those involved in the pork-barrel scam that included government agencies, lawmakers, and bogus nongovernment organizations, the Aquino administration appears to have been springing into action only after dogged media coverage on the controversy.

And when it does act, those it hales into court are mostly small fry – career civil servants from the middle level down. Interestingly, too, most of the big-fish exceptions belong to the political opposition.

Speed, volume, focus, fairness – a campaign blind to political color or friendship – these seem to be in short supply when it comes to Aquino’s anti-corruption drive. Not surprisingly, it is hard to find enough reason to assert that the present administration has conducted a truly, fully vigorous war against corruption.

For instance:

* The PDAF scam story broke in the Philippine Daily Inquirer involving eight NGOs connected with businesswoman Janet Lim Napoles in July 2013, and the Commission on Audit (COA) released its special audit report on the abuse and misuse of pork from 2007 to 2009 in August 2013.

A month later, the Department of Justice (DOJ) filed its first plunder and graft complaint against three opposition senators and five former legislators, and two months later, its second complaint against seven more former legislators.

But it was only on Aug. 7, 2015, or 24 months later, when DOJ filed its third complaint against a senator and eight other incumbent and former legislators. Curiously, all three complaints were founded on practically the same sets of documentary evidence and testimonies of whistleblowers.

* In its three complaints, the DOJ has named more than 100 respondents, including only 24 legislators mostly from the political opposition – four senators and 20 former and incumbent members of the House of Representatives. The Ombudsman has filed charges against three senators and five former congressmen in the Sandiganbayan, indicted a few more, but has yet to finish its case build-up against the rest of the lawmakers named in the three DOJ complaints.

The 24 legislators in the DOJ list make up just a fifth of the 118 legislators that COA said implemented “highly irregular” PDAF projects in tandem with questionable NGOs from 2007 to 2009.

This, in the five-year life of “Daang Matuwid” is by no measure an abundant harvest and, according to both critics and allies of the administration, an apparent case of “selective investigation” or “selective justice” on the part of the DOJ and the administration. To this day though, the Ombudsman’s Field Investigation Office continues to gather documentary and testimonial evidence against the other legislators named in the COA report.

• The COA report offered more than enough documentary and testimonial evidence on the modus operandi of legislators, implementing agencies, contractors, and NGOs, and how they corrupt the flow of public funds. Too, it proposed a menu of corrective measures and reforms that could have been instituted in agencies that have been used as pork funds conduits. The President had abolished pork barrel under the PDAF system, but in its stead allowed the continued flow of monies to bankroll projects endorsed by legislators, in the budgets of executive agencies.

• In a series, more COA annual audit reports followed for the years 2012 and 2013, this time on the same patterns of pork abuse and misuse under the Aquino administration. As with the first report, hardly word, comment, action, or promise of reform was heard from the President about what the government could do better to curb corruption.

To be sure, the problem is corruption is a problem bigger in scope and breadth than mere saber rattling against it could solve.

For one, Napoles is just one of the so-called “service providers” who have supposedly been colluding with lawmakers and officials of various state agencies to pocket funds meant for development projects. Lawyers, prosecutors, and civil servants in the agencies tainted with the corruption in pork say there are six to nine more Napoles-like “service providers.” Thus, the three batches of PDAF complaints that focused only on Napoles NGOs would hardly scratch the surface of this multi-billion-peso scam.

For another, PDAF was just one of the multiple lump-sum funds that have been raided, and continue to be raided, by Napoles and Napoles-like service providers and their fake NGOs. Audit reports documenting the abuse and misuse of these funds have not received appropriate action from the President or his Cabinet secretaries.

For a third, filing suit against a few big fish and a multitude of small fry may not at all trigger the right results and behavior among civil servants. Those in the lower ranks are bearing the heaviest punishment for corruption, even as their bosses and the politicians who authored the misdeeds have managed to fly out of the country, hide in opulent surroundings, and escape prosecution. – PCIJ, August 2015