(I did this article for VERA Files.)

The government paid $7 million in legal fees to the international team that gave the Philippines its landmark victory against China over the disputed features in the South China Sea, a member of the Philippine delegation to The Hague hearings said.

The source who asked for anonymity said the $7 million was a ceiling in lawyers’ fees the government of President Benigno Aquino III insisted on, having learned a costly lesson from the case against the Philippine International Air Terminals Co. (Piatco) where, under an open-ended agreement, the lawyers’ fees reached $65 million.

The Philippines was represented in the two-and-a half year litigation by Foley Hoag LLP. The case against China was filed with the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands on January 22, 2013.

The $7 million (P328,996,500 at P47 to $1) was the third ceiling set, more than 65 per cent higher than the original contract fee of $4,212,000 agreed upon in December 2012 by then Solicitor General and now Supreme Court Associate Justice Francis Jardeleza and Paul S. Reichler of Foley Hoag.

Reichler headed a team of six American and British lawyers from Foley Hoag, which has offices in Washington D.C, Boston and Paris.

Other members of the Philippine legal team are Lawrence H. Martin and Andrew B. Loewenstein, both from Foley Hoag ; Bernard H. Oxman of University of Miami School of Law, Miami; Philippe Sands of Matrix Chambers, London; and Alan Boyle of Essex Court Chambers, London.

Lessons from PIATCO case

In 2004, the Philippines under the government of President Gloria Arroyo nullified the contract for Piatco to build, operate and maintain the $650-million NAIA 3 terminal for a concession period of 25 years.

The Arroyo government said the company did not possess the requisite financial capacity, and that the agreement was contrary to public policy.

Piatco sued the Philippine government before the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) arbitration tribunal in Singapore for $565 million in damages.

Its foreign investor, the German firm Fraport, separately sued the government at the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in Washington.

A lawyer experienced in the litigation of private cases in international courts said counsels are paid per hour for their court appearances. He said the rate varies depending on the standing of the law firm with top-notch lawyers charging $1,000 per hour.

Adjustable cap

In the case against China, the source said the original cap of $4,212,000 was adjusted to $5,870,000 in July 2015 under a supplemental agreement that would “cover all legal services and expenses through the end of the oral hearings on the merits of the Philippines claim.”

Excluded would be “any post hearing proceedings and any extraordinary hearings such as requests for provisional measures.”

In December 2015, Foley Hoag exhausted the payment and sought another adjustment of the ceiling.

Executive Secretary Paquito Ochoa, Jr and Solicitor General Florin Hilbay expressed reservations on setting a new ceiling as it would negate the purpose of the agreement to fix a maximum amount to avoid the risk of higher and unexpected costs.

Hilbay also expressed the concern any payment outside the engagement contract might be considered illegal, irregular or excessive and may unnecessarily expose the President and other officials involved including himself to potential suits.

An increase in lawyers’ fee, however, became necessary when, in May 2016, Taiwan intervened in the case concerning Itu Aba or Taiping, the biggest feature in the Spratlys which it occupies.

Taiwan insisted Itu Aba is an island entitled to a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone that would overlap with the Philippine EEZ.

It cited numerous scholarly works in Chinese that had to be researched, translated and rebutted in a response by the Philippine legal team, as requested by the tribunal.

The Tribunal sided with the Philippines in its ruling that Itu Aba is “not capable of sustaining an economic life of their own” and is not entitled to an EEZ and continental shelf.

Debate on hiring foreign lawyers

President Aquino’s spokesman, Edwin Lacierda, defended Malacañang’s decision to hire foreign lawyers.

“We have the knowledge, but in so far as appearing before international tribunal, you get the best persons you can hire for that. It will be foolhardy for us not to hire experts with experience appearing before this tribunal,” Lacierda said.

He added the lawyers the Philippine government engaged for the historic case “have international reputation appearing before the tribunal. We can rely on them. “

Joel Butuyan of Roque & Butuyan Law Office, who has handled cases in the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes said, “The Philippines does not lack legal talent and expertise that equal those of the foreign lawyers who successfully represented the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea arbitration.”

“In fact, Philippine lawyers would have had the advantage of unequalled passion and dedication if they were given the chance to represent their country,” Butuyan said. “And certainly, Philippine lawyers would have been much less expensive.”

But he pointed out foreign lawyers come with years of actual experience handling country versus country cases, and have already addressed, researched and argued basic issues of jurisdiction.

“They have the international stature as the acknowledged experts in this kind of cases,” Butuyan said. “While stature of a lawyer does not necessarily translate into a benefit for the client, it certainly does not disadvantage the client.”

Formidable legal team

Reichler is described in the Foley Hoag website as one of the world’s most respected and experienced practitioners of public international law, specializing for more than 25 years in the representation of sovereign States in disputes with other States, and in disputes with foreign investors.

He has earned the description of being a “giant-slayer,” having humbled the United States in the case filed by Nicaragua against the superpower’s low intensity conflict campaign in the Central American country.

Former journalist now lawyer Romel Bagares, who wrote the article “The South China Sea Arbitration: the Philippines’ Nicaraguan moment” for VERA Files noted “the uncanny parallels and ironies “in the case of Nicaragua vs U.S and Philippines vs China.

“Not to be missed is the fact that Foley Hoag, the Philippines’ lead counsel in the South China Sea Arbitration is the same American law firm that won for Nicaragua respect in the world stage in its legal battle against the United States at the height of the Cold War,” Bagares said. “Both cases involved a behemoth in world politics – the United States in the 1986 case, China in the 2016 case.”

The online site The Litigation Daily named Reichler “A Litigator of the Week.” A post by Michael D. Goldhaber said, “Paul Reichler has been dubbed Mr. World Court for his dominance at the seat of public international law. But in the past week Mr. World Court became Mr. Arbitration. It was a great week for public health and maritime borders. And a terrible week for international bullies.”

Cost of Arbitration

The fee of $7 million does not include the cost of arbitration which PCA asks Parties involved in the case to shoulder.

The PCA is not part of the United Nations but is an intergovernmental organization established by the 1899 Hague Convention on the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes.

Headquartered at the Peace Palace in The Hague, the Netherlands, the PCA facilitates arbitration, conciliation, fact-finding and other dispute resolution proceedings among various combinations of States, State entities, intergovernmental organizations, and private parties.

Its rules of procedure allow the PCA to ask the Parties to deposit equal amounts as advances for the costs of the arbitration to cover the fees and expenses of members of the Tribunal, Registry, and experts appointed to assist the Tribunal, as well as all other expenses including hearings and meetings, information technology support, among many others.

Should either Party fail to make the requested deposit within 45 days, the PCA said, the Tribunal informs Parties so that one of them may make the payment.

In the Award the Tribunal mentioned that “while the Philippines paid its share of the deposit within the time limit granted on each occasion, China has made no payments toward the deposit. Having been informed of China’s failure to pay, the Philippines paid China’s share of the deposit.”

PCA said it would “render an accounting to the Parties of the deposits received, and return any unexpended balance to the Parties’ after the issuance of this Award.”

Budget Secretary Ben Diokno said he has no idea yet how much was allotted by the Aquino administration for the payment of the Arbitration Cost.

But a lawyer experienced in international litigations said arbitration cost is about $400 to $450 per hour not limited to hearing sessions, and including research and study.

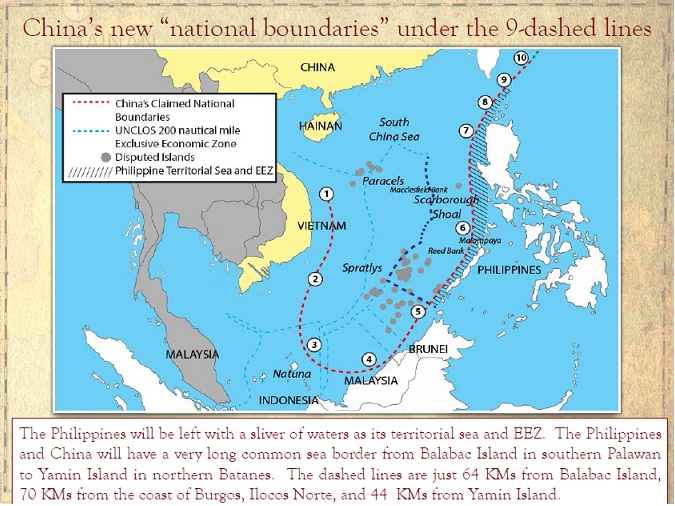

Last July 12, the Arbitral Tribunal released a decision that overwhelmingly favored the Philippines. It invalidated China’s all-encompassing nine-dash line map.

Senior Associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio, who has been advising the Philippine team and gone around the country and the word to rally support for the Philippine case, said the Tribunal’s ruling “re-affirms mankind’s faith in the rule of law in peacefully resolving disputes between States and in rejecting the use or threat of force in resolving such disputes. This rule of law is enshrined in the United Nations Charter.”

Former Foreign Secretary Roberto R. Romulo, who said the Arbitral Court’s Award provides a permanent frame to adherence to the rule of law and respect for multilateral institutions in any conversation on the South China Sea, said “whatever the cost, it was worth it.”