The following article is a reprint from Want China Times

This part is interesting (6th paragraph): ” After a new president takes office in June 2016, the Philippines is expected to postpone the arbitration and step up bilateral or multi-lateral contacts with China.”

Staff Reporter 2015-04-26 09:23 (GMT+8)

The relationship between the construction of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and the territorial disputes in the South China Sea is drawing increasing public concern along with the implementation of Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative. Observers wonder whether the disputes will produce a turning point for settling the disputes or whether the South China Sea will become the most likely area for potential conflict between China and the US. To answer the question, one should first dig out the exact crux of the disputes and then grasp the latest developments of related parties involved, particularly changes in China’s South China Sea strategies, according to South Winds, a bi-weekly magazine published in Guangzhou.

Generally speaking, the maritime disputes in the South China Sea involve six parties, namely China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia and Taiwan. Of these, Brunei has abandoned its territorial claim over Louisa Reef in the Spratlys, Malaysia has a relatively minor claim in the Spratlys, Vietnam and the Philippines make claims to major island chains while China and Taiwan maintain a similar claim to virtually the entirety of the South China Sea.

The parties are divided over whether historic rights should be applied in the settlement of disputes in the area. Before 2009, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia shared the view that disputes concerning the rights of territorial waters should be addressed based on international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), while China, Vietnam and the Philippines asserted that history should be taken into consideration. But in 2009, the Philippines reversed its attitude by promulgating its Territorial Sea Baseline Bill in line with the UNCLOS, while Vietnam and Malaysia also jointly filed a statement to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf under the United Nations clarifying their stance and assertion on the settlement of the disputes. Such concerted action by ASEAN member states to resolve the South China Sea disputes has won support from the US, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Australia and the European Union. Accordingly, China’s 9-dash line territorial claim over the entire South China Sea has come under fire from related parties and Beijing has become more aggressive in expanding military facilities to demonstrate its control of key territories as a fait accompli.

China calls it unfair to address disputes based on only the UNCLOS regardless of historical rights enjoyed by the nation before the law was signed in 1982. To avoid a stronger backlash, China has focused its oil exploration on undisputed waters around its southern island province of Hainan while being tolerant of some exploration by ASEAN states in waters that it claims.

South Winds put the Chinese case that ASEAN states have internationalized the South China Sea disputes by seeking support from the US and other countries outside the area to check the rise of China. To counter this, China has taken action to step up its control and development of South China Sea to safeguard its own interests, which were met with a series of backlashes from some ASEAN states.

In January 2013, the Philippines requested the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea to set up a tribunal to address its disputes with China. The court, established in June 2013, received an official suit filed by the Philippines in March 2014 and a supplementary document in March 2015, but China has declined to accept arbitration, denying the court’s jurisdiction. The court’s verdict is slated to be released in 2016, when a presidential election will take place in the Philippines. Now voices are rising in the Philippines that the country should take an even tougher line against China, while others are saying that as a founding member of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) the Philippines should show greater regard for economic cooperation with China. After a new president takes office in June 2016, the Philippines is expected to postpone the arbitration and step up bilateral or multi-lateral contacts with China.

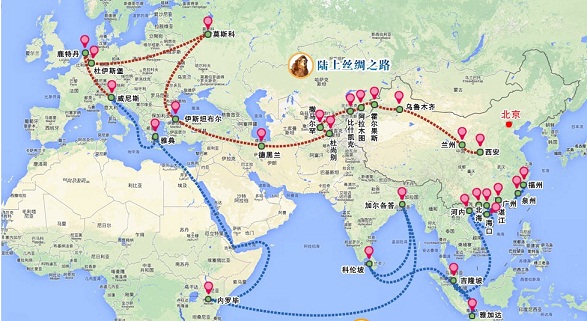

Launched in September-October 2013 by the new Chinese administration headed by Xi Jinping, the Belt and Road initiative is China’s mega external policy to guide its foreign relationships in the coming eight to 10 years and will significantly affect domestic economic development by balancing regional development, adjusting economic structures and promoting capacity transfer and industrial upgrade. Accordingly, during the construction of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, those policies running counter to the goal should be adjusted.

Southeast Asia has been an important pivot in maritime trade since ancient times. China has advocated forging a community of the same destiny with ASEAN, with annual bilateral trade likely to hit US$10 trillion in 2020 to make ASEAN the largest trade hub in the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. Accordingly, China is moving to adjust its South China Sea policy and strengthen ties with the ASEAN member states.

For instance, after removing its HD-981 oil rig from Triton Island in the Paracels in July 2014 after it prompted anti-China riots in Vietnam, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, raised a dual-track thinking formula, calling for disputes to be settled peacefully through friendly negotiations between China and related countries. In November, Premier Li Keqiang clearly set 2015 as the year for cooperation between China and ASEAN and agreed to step up negotiations on the Code of Conduct on the South China Sea (COC) with related ASEAN states.

In addition, China’s political and economic ties with Vietnam also got a significant boost when Secretary General Nguyen of the Communist Party of Vietnam paid a state visit to Beijing in early April, with Vietnam showing high interest in joining the Maritime Silk Road initiative and for the two sides to set up a joint team for promoting infrastructure construction in Vietnam. Likewise, China is also friendlier to Malaysia in dealing with South China Sea disputes.

South Winds said Indonesia, which does not have a direct dispute with China, is another country winning priority treatment from China. President Xi Jinping chose to announce his Maritime Silk Road scheme when visiting Indonesia in October 2013 and is currently paying a second visit to the country to attend the 60th anniversary of the first Asia-African Conference held in Kota Bandung. In addition, Indonesian president Joko Widodo has also expressed strong enthusiasm in joining the China-led AIIB.

The construction of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road won’t therefore escalate South China Sea disputes, South Winds said, but will instead provide a turning point for their resolution.

On another front, the South China Sea is not likely to become a flash point for conflict between China and the US as there is no substantive division in their stance on the peace, freedom of commercial navigation and the intelligence gathering rights of carrier-based aircraft in South China Sea as advocated by the US.